MY JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE

BY

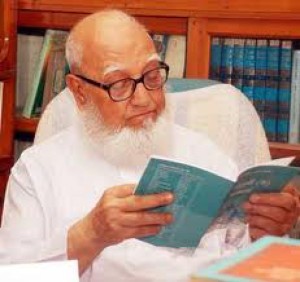

PROFESSOR GHULAM AZAM

(Abridged translation of the author’s original Bangla memoir, Jibone Ja Dekhlam)

Copyright – The Ghulam Azam Foundation

Chapter One

My Childhood

I was born in Dhaka on 7 November 1922, although I spent my childhood mostly in the village. My place of birth was a distinguished Sufi household known as Mia Shaheber Moydan (‘The Mia Shaheb Estate’) in Lakshmibazar, Dhaka, which happened to be my grandfather’s house. I was the first child of my parents, and according to the tradition of that time the first child was to be born at the maternal grandfather’s house. Hence, I was born in the city despite our family living in a village at that time. My mother made annual visits to the city (these were usually for a month or so) and so, from childhood, I became familiar with both city and rural life. I studied in village schools until Class 6. I first went to the village primary school where I remained up until Class 3. Then, in order to learn Arabic, I started from Class 3 again until Class 6 at Barail Junior Madrassah, which was in a village five kilometres away from where we lived. Thus, I was brought up in a predominantly rural environment until I was 14.

It is difficult to remember the early years of one’s life; however, I can still recollect some differences between my city and village lives of that time. While in the village, I was able to wander around my own, including in the nearby villages. During the dry season, the huge farmlands between the villages would become our playground. As our village was the centre of the local authority and not every village had a school, children from nearby villages used to study in our school. That is why I had classmates from various villages from Class 1 onwards whose homes I sometimes visited. In contrast, whenever I came to the city, I was confined to only the houses of my uncles and was not permitted to leave the family residence as for reasons of safety my elders were afraid to let me go to the main road adjacent to my grandfather’s estate. I had very few cousins of my age to play with, and as I was not allowed to leave to play with children in the neighbourhood, I would often miss my village home and would be eager to return there after a few days in the city.

I developed a strong bond with everyone in the village. Those who were of my grandfather’s age became my great uncles; those in my father’s circle became my uncles; and elders and youngsters in my generation became my elder and younger brothers respectively. I had similar relationships with the women of the older generations as well. Therefore, there were many people who could show their affection and love towards me. This was completely missing in Dhaka as I could not visit anywhere other than my uncles’ houses. Most neighbours of my grandfather’s estate in Dhaka were Hindus with whom we lacked social links. I never enjoyed having a shower in Dhaka as we had to throw a bucket into the family well to obtain water and had to have the shower next to the well, thus missing the pleasure of swimming in the river by my village. Although my mother wished to stay on in the city for a longer period, I used to long for the country after a couple of weeks in the city and I always preferred rural over urban life. I felt that I had many people who were close to me in the village who would call me towards them affectionately, embrace me and give me delicious food to eat, whereas I found no one with whom I felt as comfortable in the city except in the three houses of my uncles. There were fruit trees at hand in every house in the village. One mostly saw trees in the countryside and few houses, as if the whole area were an orchard. On the other hand, in Dhaka, I could see only buildings around me and very few trees. Therefore, I always loved the village more than the city.

Although I was more fond of country life, when the time of the year would arrive for me and my mother to visit Dhaka, I would nonetheless become quite excited. We had to take the boat very early in the morning to the railway station at Bhairab. I used become quite restless the night before and would wake up often to check whether it was morning. I used to sleep with my grandmother, who would bring me back to bed whenever I woke up and say, “I’ll wake you up in the morning, so go to sleep now”. I don’t think I ever realised at that time why I was so keen to visit the city when I would become bored there within only a couple of weeks. Now I understand that humans always like change, so wanting to move on after being in one place for a while is a natural human instinct.

The journey towards Dhaka would require transit by boat first, followed by rail. I was accustomed to boat journeys as it was the most common transport method during the rainy season in the village; so there was never anything new for me in that first stretch of the journey to Bhairab. The part I really relished was travelling by train from Bhairab to Dhaka. The sound of the train was very rhythmic to my ears and the slow, calming movement of my body inside the train was very comforting. I can still remember the rhythmic sound of the train. At the level crossing during my journey from home to the Jamaat-e-Islami office in Moghbazar, Dhaka, whenever a train passed by, I would reminisce about the memories of my childhood train journeys. While most people talk on trains, I remember that I would hardly speak a word to anyone during those childhood journeys. I savoured it to such an extent that I would never sleep on the train and would constantly gaze out the window, searching for words to describe the beauty of the scenery beyond.

The Dhaka rail station at that time was at Fulbaria, which now is a bus station. We would proceed to my grandfather’s house by a horse carriage from the rail station. Horse carriages are no longer in use in Dhaka, but I used to love the ride, where four people would sit in the carriage, two on each side facing each other. As the journey was at a steady pace, I could enjoy the scenery around me. The sound of four pairs of trotting hooves was so soothing that I liked it even more than the sound of the trains. There were no rickshaws, auto-rickshaws or cars at that time. Horse carriages were the main transport vehicle of Dhaka and you could see them in abundance across the city.

My Village

Our village is called Birgaon – as is the local authority. Travelling to our village involves taking a bus or a train to Bhairab from where you can continue by motorboat on the River Meghna to reach Birgaon. The illustrious railway bridge between Bhairab and Ashuganj was built over the Meghna River during the Second World War, when we used to travel to Bhairab to watch the construction of the bridge. Our village is four miles away from Bhairab’s river port. Throughout the dry season one had to walk a mile from the river pier in Birgaon to arrive at our house, but during the monsoon season the boat would stop just next to our house. Once I was having a particularly troublesome journey to Birgaon from Dhaka and asked my uncle, who was then headmaster of the village school, why his father had bought his house in such an inconvenient location. He smiled and said, “Our family have been living here even before my grandfather. At that time most trips would be done on water, so people built their homes near the river”. As a student of social science I later realised the historical truth of this fact.

During those days most people would go to work in the field following the morning prayer and reading the Qur’an. I could hear the sound of Qur’an recitation from every single house whilst going to the mosque in the morning to read the Qur’an. This custom is almost lost now. The person who gave the call to prayer was our next door neighbour, Mr Aziz Ullah Munshi. There was no loudspeaker at that time, but Mr Munshi was a loud speaker himself and it was believed that people could hear his call to prayer from over a mile away.

There is a tradition in the villages of Bangladesh of bringing gifts such as vegetables or fruits from one’s own garden, or eggs laid by one’s own hens, or milk of one’s cows, and so on, to a Sufi leader or to the mazar (burial ground) of a spiritual leader or to a spiritual leader himself. As my grandfather was a celebrated Islamic scholar, people began to bring gifts for him. My grandfather then declared in one of his Friday sermons that such gifts should be brought only for the mosque. He introduced a wonderful practice where people would bring their gifts to the mosque on Fridays, and after the prayers an auction would take place at the mosque to sell these items (with the proceeds going towards the mosque fund).

There was no practice in our village of greeting everyone with salam1, although people would generally say salam to an Islamic scholar. A political leader would be greeted with adab, a type of greeting introduced by Hindus. People would talk to each other when they met, but the custom of salam was reasonably limited at that time. When I was a student of Barail Junior Madrassah our teachers encouraged us to greet each other with salam. I tried to practise this in my village and once greeted a political leader called Daru Miah with assalamu alaikum (peace be on you). He replied to my greeting with his hand, but I didn’t hear him say wa alaikumus salam (peace be on you too). Daru Miah was a prominent leader of the Indian National Congress in our local authority who was very well acquainted with my father. After my salam incident he was heard saying that I had become quite ill-mannered as I had failed to greet him with adab.

Whether Hindu or Muslim, all gentlemen wore a dhutti (loincloth) at that time except those who were Islamic leaders. I remember that I once received a loincloth as a gift. Muslims stopped wearing loincloths after the Pakistani movement had become prominent. During weddings aristocratic individuals would wear a sherwani2 and a round tall hat called a rumi.

My District and Sub-District

The name of my sub-district is Nabinagar3-a name that fills my heart! What better name could a place have? I am unaware of the history behind this name, but it certainly carries a Muslim identity. However, the name of my district is quite the opposite. Though my sub-district is Nabinagar, but it is under the dominance of Brahmins4. That is, my district is called Brahmanbaria or in short Bbaria. I do not know the history behind this name either. I read an article on the subject in a monthly magazine called Brahmanbaria Sangbad (Brahmanbaria News), but whatever the writer wrote based on legends and hearsay certainly cannot be considered as history. However, there is no doubt that the Brahmin community must have dominated this place before, hence the name.

I grew up observing the prominence of the Hindu community; many became successful in sectors such as education, employment, business, land ownership and beyond by assisting the British imperialists. Next to our local authority of Birgaon is Krishnanagar, where there was the house of a Hindu landlord surrounded by huge walls. When I was small I heard that Muslims were forbidden to pass by that house wearing their shoes or with their umbrellas open. Without the Pakistani movement for Muslim nationalism and without the partition of India in 1947, Muslims in this land would still be restrained by Hindu dominance.

1 Muslim greeting: assalamu alaikum (peace be with you)

2 A type of suit including trousers and a long coat worn in South Asia by aristocrats

3 Literally meaning ‘Prophet’s Town’

4 Upper class Hindus

very nice writing. i had raed it before but by reading this time i feel very proud and the heartest love and honour for our leader