Home » Posts tagged 'autobiography'

Tag Archives: autobiography

My Journey Through Life Part 20: Joining Tamaddun Majlish

MY JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE

BY

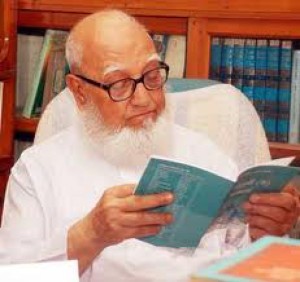

PROFESSOR GHULAM AZAM

(Abridged translated version of the author’s original Bangla memoir Jibone Ja Dekhlam)

Translated and Edited by Dr Salman Al-Azami

Copyright – The Ghulam Azam Foundation

Chapter Twenty

Joining Tamaddun Majlish

In mid-1952 a person named Sulaiman Khan of Tamaddun Majlish came to see me at my Rangpur College campus home. He came all the way from Chittagong[1] just to see me. I was surprised and asked him the purpose of his visit and was told that he came to talk about Tamaddun Majlish[2].

I cordially invited him into my house upon hearing the name Tamaddun Majlish. I had heard about this organisation many times when I was politically active in Dhaka University in 1948. During the Language Movement I used one of their books called Is Pakistan’s State Language Bangla or Urdu? (Pakistaner Rashtro Bhasha Bangla na Urdu?) during the campaign to establish Bangla as a state language. I had also seen the founder of the organisation, a young lecturer of Dhaka University, Mr Abul Kashem, several times although I was never formally introduced to him.

Mr Khan stayed with me for two days. As my wife was not at home we spent a lot of time together and discussed many things and soon became close friends. I was impressed by his sweet smile, conversational style, and his ability to speak eloquently. I developed deep love for him as a brother of deen (religion). He told me that the Tablighi Jamaat teaches the meaning of the Kalimah[3]; that there is no other god than Allah, and teaches the oath that one will spend one’s life obeying Allah’s orders following the path of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). This is obviously correct in terms of wordings, but when they use the word ma‘bud to mean ‘someone to worship’ only and the word ibadah (worship) is confined to some religious rituals then this Kalimah bears little revolutionary significance. Therefore, the fact that the oath in the Kalimah is applicable to all walks of life is not highlighted much by Tabligh, although it instils the sense that the promise in the oath has to be kept.

This little speech of brother Sulaiman shook my conscience and touched my heart. He reminded me that we also need to lead our social and economic lives by obeying Allah in the path of the Prophet (PBUH), highlighting the fact that our Prophet himself led a huge revolution in his land of birth on the basis of the Kalimah. That Tamaddun Majlish called upon people with the message of this revolution left me no other option but to join them. I had never received this type of message before. I completed the membership form of the organisation and took the responsibility to develop and lead it in Rangpur. He left some books with me, which I bought from him. I found two key points about the movement from those books – the sovereignty of Allah and that He is the owner of all our wealth.

Sovereignty of Allah

As a student and then a teacher of political science, I knew the word ‘sovereignty’ very well as an important terminology in the discipline. One of the four core components in the definition of a state is sovereignty. The book, The Grammar of Politics, written by a famous British political scientist, Professor Harold Laski, was my textbook at MA level. In its chapter on ‘Location of Sovereignty’ he proved that there is no such thing as a ‘sovereign force’ in a state. It is not possible to find out where to find the features of sovereignty that political science speaks of. I knew this concept very well and had to teach sovereignty as a key term in my discipline to my students.

In fact, I was a bit perplexed about how to go about with this concept as I was a strong supporter of Laski’s theory. After getting the solution of the term through Tamaddun Majlish I began to invite people to this movement making the sovereignty of Allah as the key point in my discussions. The attributes of Allah found in Ayatul Kursi[4] are similar to quite a few features of sovereignty in political science. I realised that Laski’s confusion on the concept can only be resolved by accepting Allah as the sovereign entity. I also acquired the book Political Theory of Islam by Mawlana Mawdudi through my involvement with Tamaddun Majlish. My concept of sovereignty became clearer after reading that book and I started lecturing my students based on my renewed understanding of the concept.

I developed a partial understanding of the second point of brother Sulaiman’s speech that Allah is the owner of all our wealth, which can be found in the verse: ‘Allah is the owner of everything in the heavens and the earth (lillahi ma fis samawati wama fil ardh)’.[5] Therefore, Islam does not believe in personal wealth, which is the basis of a capitalist economy leading to economic oppressions in a society.

The political mission of Tamaddun Majlish was clear to me and, as it was related to my academic discipline, I decided to concentrate my calls to the organisation on this point. As I was not yet very clear on the economic aspect, I decided to know more about the area before speaking about it.

Serving Two Organisations Simultaneously

I continued to serve both Tablighi Jamaat and Tamaddun Majlish simultaneously as the leader of their Rangpur chapters, emphasising the importance of both organisations. Tablighi Jamaat remained central to me in terms of spirituality, while I continued to call people towards Tamaddun Majlish highlighting its political and economic thoughts. I was satisfied that both these organisations were able to lead me to the establishment of Islam in my life. I still remember that I once took some posters of Tamaddun Majlish while going on a Tablighi chilla.

Islamic Cultural Conference

After joining Tamaddun Majlish, my first opportunity to attend a major programme of the organisation was the Islamic Cultural Conference held at the famous Curzon Hall of Dhaka University in October 1952. The three-day conference was presided over by the President of Tamaddun Majlish and a professor of philosophy, Dewan Mohammad Ajraf, while the conference was inaugurated by the editor of Daily Tasneem of Lahore, Mawlana Nasrullah Khan Aziz. I was asked by the founder secretary of the organisation, Professor Abul Kashem, to bring the guest from Lahore to the conference venue from 205 Nawabpur Road where Jamaat-e-Islami office was at that time. He gave his inaugural address in refined Urdu, which I didn’t understand very well as I had only learned enough Urdu to carry basic conversation. However, I did understand the spirit of Islamic movement in the speech.

As already mentioned, I understood the concept of Allah’s sovereignty very well, but was not very clear about the concept of Islamic economics while working with this organisation. In the session on social science in the conference, I became a bit worried about the content of a speech by one Mir Shamsul Huda whose topic was, ‘Allah + Marxism = Islamic Economics’ where he clearly announced that we can accept a Marxian economic system as Islamic. Although Karl Marx was an atheist, he suggested that if we just avoid the atheistic concept of Marx, then there is no problem. I had read and initially liked a book written by the Chair of that session, Mazharuddin Siddiqui, entitled Economic System of Islam, and liked some aspects of it, but when I came to know that he accepted Socialist economics as Islamic I lost interest in it. It seemed that due to the lack of knowledge on Islamic economics, even some Islamic scholars considered socialism as an alternative to capitalism.

Knowing Islamic Economic Systems

I spent 15 days during the Ramadan of 1953 at a training camp of Tamaddun Majlish where I realised that they loved Islam with sincerity and had strong faith in Allah, the Prophet (PBUH) and the Quran. They were also very keen to learn about Islam, but as there was very little Islamic literature at that time they struggled, like I did, in developing in-depth knowledge of Islam. I was particularly concerned that my knowledge about the Islamic economic system remained unclear.

We had the impression that two fundamental aspects of socialism can be found in Islam

- Personal wealth is the foundation of capitalist oppression, so it is not natural for Islam to support personal wealth, because Islam cannot support oppression. We thought that the verse lillahi ma fis samawati wama fil ardh, which means ‘whatever exists in the heavens and the earth belongs to Allah’[6] is a straightforward announcement against personal wealth.

- We also thought that labour was the only cause for production. Socialism does not accept personal wealth as the ‘cause of production’ because of its hatred towards capitalist economics. We used the verse laisa lil insani illa ma sa’a, which means ‘man can have nothing but what he strives for’[7] to support this principle. The essence of this principle was that only labour is the source of production and that no one has the right to any wealth without labour.

I was able to gain real knowledge of Islamic economics in 1956, two years after joining Jamaat-e-Islami in 1954. This was when Mawlana Mawdudi came to the then East Pakistan for the first time. I arranged a meeting between Mawlana Mawdudi and Professor Abul Kashem at the request of the latter where these two verses were discussed in details. When Professor Kashem tried to justify labour as the source of production citing laisa lil insani illa ma sa‘a as the basis, Mawlana Mawdudi said, “Brother, wherever this verse has been used in the Quran, Allah used it for life after death. People will only get on the Day of Judgment that which they have earned in this world; so one will neither be blamed for someone else’s sins, nor will they be benefitted by other people’s good deeds. If you apply the socialist principle then children, old people, disabled – no one can have any wealth. They would have no right whereas Allah has categorically given them their rights.”

When Professor Kashem reminded that Islam does not support personal wealth as declared in the verse lillahi ma fis samawati wama fil ardh, Mawlana Mawdudi said, “Allah Himself has given the right to inheritance after the death of a person. He has allowed personal wealth. This misconception has been created due to not understanding the verse properly. Allah is the supreme owner and the ownership of human beings is controlled by Allah’s doctrines. Through that verse Allah tells humans that you are not the supreme owner of your wealth that you can use them however you like. Allah is the ultimate owner of your wealth and it is He who has given it to you, so it is the responsibility of human beings to follow the instructions of earning and spending wealth. Capitalism has been created due to violating those instructions, which has led to public being oppressed by the privileged few”.

I Have Always Loved Tamaddun Majlish

Although I left Tamaddun Majlish and joined Jamaat-e-Islami, I have always had a good impression about the organisation and never said anything negative about them. I have written in several books how grateful I am to the organisation as it is my involvement with this organisation that led me to join the Islamic movement.

After Mr Abdul Khaleq invited me to join Jamaat-e-Islami in 1954, and after reading two Urdu books he gave to me, I could feel that someone was dragging me to that organisation. I was satisfied with the spiritual side of Tabligh and the political side of Tamaddun Majlish, but when I realised that both could be found in Jamaat-e-Islami, then I decided to leave both these organisations and get involved in all aspects of Islam in one organisation rather than being involved in two.

Given my closeness to the Tablighi Jamaat, I am doubtful about whether I would have joined Jamaat-e-Islami had I not been involved with Tamaddun Majlish. I sincerely acknowledge the contribution of Tamaddun Majlish for paving the way for me to join Jamaat-e-Islami. I am forever grateful to Tablighi Jamaat and Tamaddun Majlish for their contribution towards my life as a Muslim. Tablighi Jamaat gave me the spirit of missionary work while Tamaddun Majlish made me the understanding Islam as a movement for social revolution. I first heard the term ‘Islamic movement’ from Tamaddun Majlish.

If brother Sulaiman had not come all the way from Chittagong to invite me to Tamaddun Majlish, I would not have joined it only by reading their literature. Similarly I would not have joined Jamaat-e-Islami had I not been approached by Mr Abdul Khaleq. From my own experience I have come to learn that people may be influenced by the speeches at public meetings or other gatherings, but no one joins an organisation if they are not personally approached by someone.

[1] A major coastal seaport city and financial centre in south eastern Bangladesh.

[2] An Islamic cultural organisation in Bangladesh, established in 1947 in erstwhile East Pakistan, which founded the Bangla Language Movement.

[3] The first article of faith in Islam.

[4] The Throne Verse or Ayatul Kursi, is the 255th verse (ayah) of the second chapter (sura) Al-Baqara in the Quran. It is one of the most famous verses of the Quran and is widely memorised and displayed in the Islamic world due to its emphatic description of Allah’s power over the entire universe.

[5] Quran (4:131)

[6] Quran (4:131)

[7] Quran (53:39)

My Journey Through Life Part 13

MY JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE

BY

PROFESSOR GHULAM AZAM

(Abridged translated version of the author’s original Bangla Memoir Jibone Ja Dekhlam)

Translated and Edited by Dr Salman Al-Azami

Copyright – The Ghulam Azam Foundation

Chapter Thirteen

Involvement in Sports

I remember playing some sports, like kabbadi1, gollachut2, athletics, kite flying and so on during my primary school years in our village, among which kabbadi was the most popular. Watching elders play football, we also became interested in it, but didn’t have a ball to play with, so we used an unripe grapefruit as the ball. Observing our interest in football, my grandfather asked a cobbler to make a leather football for us with cotton inside it so that we could play in our own backyard rather than with the mischievous boys of the village. He used to be the referee sitting on the veranda while we played. When I was at Barail Junior Madrasah I used to love the PE3 lessons and used to practice them with others at leisure time. There used to be competitions in kabbadi, football and athletics, but I was not as good as others in those sports.

I continued to enjoy the PE lessons while at Comilla High Madrasah and also played football when there was no PE. I was never good at football, but I always loved the sport. During 1938-39 when I was in Class 7 or 8 I used to go to a local English landlord’s house with my friends to listen to the football commentary on the radio between Mohammedan Sporting and Mohun Bagan football clubs in Kolkata. Mohammedan Sporting was for Muslims while Mohun Bagan was a club for Hindus. Politics and sports were closely related to each other during that time, so a victory of Mohammedan was considered to be a victory of Muslims, making football an influential sport in nurturing Muslim nationalism. The Daily Azad, established by the legendary Muslim journalist Mawlana Akram Khan, used to make big headlines when Mohammedans won a match. When elders read those stories aloud we would all listen to hear about the performances of our heroes. I still remember the name of a famous player called Jumma Khan, a Punjabi player with a bulky physique. I also remember a line from a report in the Daily Azad that showed how the newspaper and Mohammedan Sporting were closely related to our Muslim sentiments at that time. It said, “Who can stop Mohammedan’s victory? Hafez4 Rashid is playing with the Qur’an in his heart!”

I used to go and watch annual sports competitions of some famous schools at that time. I never tried to be a sportsman, probably because I didn’t think I had the potential, but I enjoyed watching others play. When I was in Comilla I once collapsed with sunstroke while watching the annual sports of a Hindu school called ‘Ishwar Pathshala’.

I used to play volleyball regularly while I was in Koltabazar Hostel in 1940, and continued to play the sport the following year in the college ground. I realised that although I was not good at football, I played volleyball quite well. While I was staying at Paradise Hostel during 1941-42, I could play volleyball at the hostel premises rather than having to go to the college ground. In the absence of the required equipment for volleyball we would play badminton, which I liked even better. I had a slightly taller friend called Amin Uddin with whom we formed a doubles team, calling ourselves ‘Hopeless’, and we won the college championship that year. The principal was very amused at our name and while giving his speech during the prize giving ceremony he said, “The doubles team of Ghulam Azam and Amin Uddin were so confident of winning that they called their team ‘Hopeless’ to surprise everyone.” Our ‘Hopeless’ team was revived in 1944 when Amin Uddin and I were in the same student hall (Fazlul Haque Muslim Hall) of Dhaka University. We maintained our reputation by becoming the hall champions for two consecutive years. Our team ended naturally after Amin Uddin left university in 1946.

I also played volleyball regularly during the dry season in the hall compound. When I went back to Chandina for holidays I played both volleyball and badminton in the high school grounds there and became known as a good player in both these games.

Post-Education Life

I formed a badminton doubles team with Professor M R Helali of the English department while lecturing at Rangpur Carmichael College, although we never took part in a competitive game. I also played badminton, having been inspired by a Jamaat leader when I was in Lahore Jail in 1964, with other central leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami after the then President Ayub Khan banned Jamaat. We used to play against each other and leaders like Mawlana Mawdudi and Mawlana Abdur Rahim used to enjoy our competition and acknowledged that we were good players. As I used to win most of the time, they wanted to know whether I had played badminton during my student life and I had to confess that I had been the doubles champion in my hall. I was later transferred to Dhaka Central Jail upon my request so that I could see my family every fortnight. There were no badminton facilities there, but I would play rings with one of the Jamaat leaders there.

Watching Sports

Although cricket is the most popular sport in our country, I still like football more. Unlike cricket, one doesn’t have to wait long to get a result in football. Sometimes a cricket match continues for days and the crowd sit and watch the game for a long period of time. It may be worth it for players to watch the game like this in order to learn and devise tactics, but I have to admire the patience of the crowd who spend such a long time watching the game. I definitely don’t have this strange patience. It is not only in stadiums; many people stop their work and watch the game on television for hours and hours. As the results and analyses of these matches take up prominent spaces in newspapers, I also read some of them and try to find out who is winning. However, I don’t have the competence of a supporter or a follower of the game like others.

My Views on Sports

I have my own perspective on sports. I feel that sports have a role to play in physical activities and entertainment and some people may be very passionate about them, but I find it difficult to understand why people would take up sports as a profession. Many players in the world have a huge income as professional players and don’t need to be involved in any other profession. I also acknowledge that some players have improved the sports they play at a very high level and have achieved remarkable feats. However, as a believer of life after death I wonder what these people will answer to Allah when asked what they did in this world. Is the purpose of this life just to play? Should one choose sports as their primary way of life? On the other hand I do admit that sports can inspire the youth and they can play positive roles in the society. Elderly people are also inspired by sports and can enjoy it as a form of entertainment. From these perspectives one cannot ignore the significance and contributions of sports in the life of citizens.

Amazing Popularity of Cricket in Bangladesh

As already mentioned I am not fond of cricket and don’t waste my time watching the game. However, everyone in my house loves the game and although their over-enthusiasm sometimes annoys me, I don’t stop them from enjoying. One of the pleasures of watching a game is shouting and yelling with other compatriots. Those who are unable to go to the stadium become their spiritual comrades watching it on TV. When all of this happens, I find myself isolated and unwanted in my own house.

My younger brother Dr Ghulam Muazzam is also a fan of cricket, as are his sons and grandchildren. They are not only fans, but cricket analysts as well. As my brother is not as boring as I am in terms of sports, his grandchildren are even better skilled in the sport than their grandfather. My youngest son Salman used to play cricket when he was a student and loves the sport. When I was in Dhaka Central Jail in 1993, Salman’s newly published book Bishsher Shera Cricket O Cricketor (The World’s Best Cricket and Cricketers) reached me. I was in the VIP jail cell, called ”26 Cell”, where most of my cellmates were cricket fans as well. They almost snatched the book from me before I could read it, so I had to be the last person to read the book. Although I am not fond of cricket, I read most parts of the book and found it an enjoyable read. Salman claimed in his book that cricket can be a force to unite this world and wrote in his introduction:

“Cricket has conquered the world. It has brought the whole world together – not through the power of weapons, but through the beautiful means of discipline. (…) How beautifully cricket has transcended geographic boundaries and united the world! It has brought people together by destroying their differences in terms of race, language or culture. (…) I read in the religious scripture that ‘Allah is beautiful and He loves beauty’. We can’t see Allah, but we can feel His beauty by seeing His beautiful creations. Cricket is one such beautiful creation of Allah and we bow down towards Him for gifting us this beautiful game”.

Although I am not influenced by Salman’s philosophy and deep emotion towards cricket I do acknowledge the huge popularity of the game.

Cricket Politics

When in 1999 Bangladesh beat Pakistan in the Cricket World Cup in England, the Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina commented, “This victory was possible because the players played with the spirit of 1971.” However, Bangladesh was defeated by Pakistan the following year in Dhaka with Sheikh Hasina present in the ground. I could not understand why she herself could not bring that spirit back to our players.

Cricket is just a game and she made herself a laughing stock by bringing the Liberation War into the game. Bangladesh’s victory was not due to the spirit of 1971, neither was their defeat because of the lack of it. Victory and defeat in sports depend on performances on the ground – nothing else.

India and Pakistan are top teams in world cricket. Pakistan has won more matches between them than India, but I am not sure whether the ‘spirit of 1947’ had to do anything with their success against their arch rivals. When these two teams play against each other in Dhaka, most people support Pakistan. My impression is that this support is more to do with people’s negative attitude towards India than their love towards Pakistan. Awami League leaders consider India their close ally despite most people in Bangladesh supporting teams that oppose India. Does this mean most people in Bangladesh are Razakars5? Who are the patriotic people then?

I can see similar political significance in India-Pakistan cricket matches to that which I used to witness between Mohammedan Sporting and Mohun Bagan football clubs during my student life.

1 A traditional sport in rural Bangladesh, also played in wider South Asia and is a competitive game played at Asian Games.

2 A traditional rural sport that is less played in modern times.

3 Physical Education

4 Someone who has memorised the whole Qur’an by heart.

5 A pejorative term referring to members of a paramilitary force created by the Pakistan Army during the Liberation War of 1971.

My Journey Through Life Part 11

MY JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE

BY

PROFESSOR GHULAM AZAM

(Abridged translated version of the author’s original Bangla Memoir Jibone Ja Dekhlam)

Translated and Edited by Dr Salman Al-Azami

Copyright – The Ghulam Azam Foundation

Chapter Eleven

Literary and Cultural Activities

As mentioned before my teacher in junior madrasah Mr Shamsuddin sparked my interest in reading for which I will never forget him and will continue to pray for him from the core of my heart. I would take books from the madrasah library and continued to do so while in high madrasah, although there was no one like Mr Shamsuddin to guide me to which books to read. When I was in Islamic Intermediate College in Dhaka I again started taking books from its library, and upon observing my progress in Bangla in the half-yearly exam, the Bangla teacher Mr Aminuddin suggested that I should read the short stories of Rabindranath Tagore[1] to improve my Bangla. I was startled by the beautiful literary style, linguistic elegance and philosophical teachings of those stories. My eldest two sons Mamoon and Ameen were students of Dhaka College in 1971. As the situation in Bangladesh was not good, in 1972 they and my brother Dr Ghulam Muazzam’s eldest son Suhail went to England to study there. When I met them in 1973 after two years I realised that there was no scope for them to practice Bangla in that country. At that time I remembered the prescription of my Bangla teacher Mr Aminuddin and arranged to bring all the volumes of Tagore’s Galpaguccha (Collection of Short Stories) from Bangladesh.

I became very attracted to Bangla novels while studying at intermediate level and, upon seeking Mr Aminuddin’s advice, he suggested I read Saratchandra’s novels. Before sleeping, I would read non-academic books, but the storylines in novels were such that it was difficult to go to sleep before finishing a novel. Lack of sleep was beginning to affect my studies, so I went back to Mr Aminuddin for advice. He shook my shoulder and said, “Make a decision that you will not read for more than an hour before sleep, and when it is time to sleep you will stop reading. You need to know how to control your mind.” This advice was instrumental in aiding me to strike a balance between reading and sleeping.

When I was in secondary school I was fond of the poems of Kazi Nazrul Islam[2] in my textbooks. My cousin and classmate Abdul Quddus sang Nazrul’s songs well and I obtained Nazrul’s poetry collections through his help. We would organise internal programmes where Abdul Quddus would recite Nazrul’s poetry, which had all the ingredients to attract the youths – revolutionary poems that would inspire us tremendously. I was introduced to Rabindranath’s poetry in university. Tagore’s Sonar Tori (The Golden Boat) was our text in Bangla literature, which was beautifully taught by Professor Biswaranjan Bhaduri. He talked a lot about Tagore’s poetry, so I asked him to recommend books that would inform me on the famous poet’s work. He told me to read a book of poetry criticism called Rabirashwi (The Light of Rabi) through which I became a fan of Tagore’s poetry as well. His poems were completely different from those of Nazrul in terms of language and content. They were both beautiful flowers for me, but with different fragrances. That is why the appeals of Tagore’s and Nazrul’s songs are very different. Nazrul is the national poet for Bengali Muslims while Tagore is the emperor of Bangla literature.

As I was intrigued with Bangla literature I was not contented with only two lectures a week in university. Only those who took a module called ‘Special Bengali’ could attend six hours of Bangla lessons a week. However, I came to know that there was a class on novels taken by Professor Ashutosh Bhattacharya, which did not clash with any of my lectures and I started attending it with his permission. He would analyse the characters in Bankimchandra and Saratchandra’s novels, and as I had read the novels before, I really enjoyed the discussions. I soon became his favourite student, despite not being an enrolled member of his class, due to my enthusiasm and ability to answer different questions. I later achieved the highest results in Compulsory Bengali in my BA final exam held in 1946.

Involvement in Literary Organisations

I was actively involved with the East Pakistan Literary Society and was its assistant secretary when Sardar Fazlul Karim[3] was its secretary. I was very close to the president of the society Qazi Motahar Hossain[4] as he was my house tutor in our student hall. I later became its secretary in 1948 during my MA. My relationship with Syed Ali Ahsan[5] and Syed Ali Ashraf[6], the two famous brothers, developed during my activities with this organisation. I was very lucky to have acquaintances with some legendary figures of Bangladesh like poet Kaykobad[7], Professor Ibrahim Khan[8] and many more due to my involvement with this organisation.

Since my boyhood I had been fond of Nazrul’s Islamic songs sung by singer Abbas Uddin[9], and although I never tried to be a singer, I would often sing those songs myself. I read Tagore’s Gitanjali[10] (Disambiguation) after my BA exams and memorised some of my favourite poems and would recite or sing them alone sometimes with great pleasure. When I read the Masnavi by Mawlana Rumi[11] I discovered that it had a lot of similarities with the poems of Gitanjali. Later, while reading works of Swami Vivekananda[12] I came to know that Tagore was greatly influenced by Mawlana Rumi’s works and would often recite his Persian poetry aloud in his room. The poems of Gitanjali are devoted to the Creator with songs on surrender to God, supplication to Him, emotive appeals to the Creator and immense love for the Almighty. Whilst in jail in 1964 I wrote some of these emotional poems in a diary and have retained the diary all my life. I was surprised that the materialistic people in the West decided to award the Nobel Prize for a book of religious nature, and came to the conclusion that there is an underlying belief in the divinity behind the so-called materialism they claim to possess.

The anti-Muslim sentiments that are found in Tagore’s writings are political thoughts of an Indian Hindu. He acted against Muslim interests by being strongly against ‘Bangabhanga’ (The Partition of Bengal). He was guided by Hindu nationalism, so only the inhabitants of this country who possess Bengali nationalism and are Indian in their hearts can ‘worship’ him as their national poet instead of our actual national poet Nazrul Islam; those who believe in Bangladeshi nationalism do not think in this way.

I am not a litterateur or a cultural activist

I love literature, but I am not a litterateur; similarly I am fond of good songs, but I am not a cultural activist. Those who become inherently litterateurs start writing from a very young age. As practice makes one a singer, continuous writing makes one an author. If I was inherently a litterateur then I would have been writing from my student life. Despite being actively involved in the East Pakistan Literary Society I did not develop the habit of creative writing. I only remember writing a piece of political satire called ‘Indian Politics in the Hereafter’ for the Dhaka University Magazine in 1946. It was an imaginary discussion after death between prominent politicians of British India like, Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah, Patel, Mawlana Azad, Subhash Basu and so on.

I consider myself as a person who loves literature, but due to my active involvement in the Islamic movement I have not been able to enjoy literature as much as I would have liked for many years, which I do deeply regret. I have been reading in Bangla, Urdu and English, but they do not fall under the category of literature that I previously enjoyed. Thus, despite being fond of literature, I never consider myself a litterateur. This is not because I am trying to be modest, but due to the fact that my writings have not been written for literary discussions, but for the sake of propagating Allah’s Deen. My political books are also for the cause of Islam. I am rather close to poet Al Mahmud[13] due to our ideological positions and it was he who inspired me first to write my memoirs. He once strongly protested when I claimed that I am not a litterateur. Despite his disagreement I have not changed my mind.

The Bangla first translation of Mawlana Mawdudi’s Tafheem ul Qur’an (Towards Understanding the Qur’an) was done by Mawlana Abdur Rahim. His language was of a high literary standard, but it was difficult for the less educated activists of Jamaat-e-Islami to understand. When I voiced my concerns he said, “I have intentionally made the language difficult as I want to prove that Islamic scholars can have good literary standard as well.” He is successful from that perspective, but my thoughts are a bit different as I wanted the translation to be easy for everyone to understand. I started translating Tafheem ul Qur’an from Urdu into simple Bangla myself and began with the final part of the Qur’an. After it was published in 1982 I sent a copy to Mawlana Abdur Rahim for his comments. He wrote, “The language of the last part of the Qur’an is of high literary standard, so its translation should also be of high standard. You have insulted it by using the language of common people.” I replied saying, “I have no objection to the perspective from which you felt this way, but at the same time I think I have received confirmation from you that the general public will be able to understand my translation.” This story proves that I am not a litterateur and do not write for literary purposes. Therefore, I have never been concerned with the literary standard of my writings. However, it was reassuring when Professor Syed Ali Ahsan praised my translation and told me that he had liked my translation of the last part of the Qur’an more than any other translation he had read.

Cultural Field

I am not only culturally-minded, I am also very fond of cultural works, but I have never been culturally active. The word ‘culture’ is very broad and I am referring to its narrow meaning that refers to literature, poetry, drama, music, art, etc. Many people may become infatuated by literature when they are young, but that craze later disappears when they enter professional life. My younger brother Ghulam Muazzam loved poetry when he was in Class 9, but could not sustain that interest when studying medicine. I also had my poems published in school magazines. I even wrote a few poems dedicated to Allah while in Dhaka Central Jail in 1964. I kept it a secret from my prison cell colleagues. Whereas, if I was a poet I wouldn’t have been able to help but read my poems aloud to my colleagues.

There were stage dramas while I was actively involved in Dhaka University hall union, and I even helped manage some drama programmes, but I never felt the urge to do any acting. I acted in two plays in my life, once when I was in Class 5 and the second time when in Class 9.

I was also not a singer, but I liked to sing. It is rare to find a person who has never sung in their life. However, I would not take part in public singing. Whilst doing my undergraduate I once visited Kolkata and spent a few days in one of my uncle’s houses. I was given a separate room and one day I started singing aloud thinking that nobody could hear me. After dinner my aunt took me to the roof of the house. It was a moonlit night with a nice breeze in the month of June 1946. I discovered that my school-going cousin had brought a mat and a pillow to the roof. I was not sure what was happening. Then my aunt said, “My dear, you have a very sweet voice. Please sing an Islamic song for me.” I became surprised and felt extremely embarrassed. She continued, “You can’t avoid this. I have heard you singing and I was very impressed. Please sing those songs for me”

I had never imagined that I could be caught in this way, so I sang a famous Nazrul song dedicated to Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). My aunt was so impressed that she asked me to sing another song and I obliged by singing another Nazrul song. I had never sung in this manner in the presence of others, but gradually I started to feel confident and sang a few more songs. I had not noticed that people started to gather around the roofs of neighbouring houses and were quietly listening to my songs. I felt very uneasy and, with my aunt’s permission, quickly returned to my room. I almost forced myself to leave the house and go to my uncle Shafiqul Islam’s hostel early the next morning.

[1] The most famous Bangla litterateur who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913.

[2] The National Poet of Bangladesh famous for his revolutionary works against the British Empire and for his Islamic songs.

[3] A famous 20th century scholar, academic, philosopher and essayist in Bangladesh.

[4] A renowned author, scientist, statistician and journalist in Bangladesh in the last century.

[5] Former National Professor of Bangladesh.

[6] A famous educationalist and founder of Darul Ihsan University in Bangladesh.

[7] A Bengali epic poet and writer of the 19th and 20th centuries.

[8] Another legendary litterateur in Bangladesh.

[9] A legendary Bengali folk singer and composer during British India.

[10] A compilation of lyrical poems that earned Tagore the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913.

[11] A Persian Sufi saint and poet.

[12] A Hindu monk, philosopher and chief disciple of the 19th century saint Ramakrishna.

[13] One of the most prominent of contemporary Bengali poets and litterateurs

My Journey Through Life Part 10

MY JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE

BY

PROFESSOR GHULAM AZAM

(Abridged Translated version of the author’s original Bangla Memoir Jibone Ja Dekhlam)

Translated and Edited by Dr Salman Al-Azami

Copyright – The Ghulam Azam Foundation

Chapter Ten

Contributions of Two Great Scholars

Mawlana Shamsul Haque Faridpuri

As mentioned in the previous chapter, I used to visit the office of Monthly Neyamot regularly after starting my education in Dhaka and developed a special rapport with its editor Mr Abdus Salam. Mr Salam informed me that Mawlana Shamsul Haque Fardipuri was a teacher at the Boro Katra Mosque in Dhaka and suggested that I could meet him following the afternoon prayer at Chakbazar Mosque any day. I went to see him accordingly and found him surrounded by some people who were asking him questions on Islamic jurisprudence and he was replying to them briefly with a constant smile in his face. Some people were also asking his advice on their personal problems. I realised that people loved and respected him like a sufi leader.

I was sitting quietly amidst older and knowledgeable people and felt a bit overwhelmed as I was only a teenager in front of a great Islamic scholar. I kept looking at him and wondering how to approach him, and noticed that he was also staring at me while answering other peoples’ questions. After he dealt with all the questions that day he signalled me to go near him. He shook my hands and asked me the reason for my visit. I was waiting for this opportunity and kept talking to him for a few minutes while the elders around me looked surprised at how a scholar like him was listening to a young boy with such interest. I told him how I was introduced to Mawlana Ashraf Ali Thanvi’s works in the Neyamot magazine through his translations and asked him where I could find his books and whether I could visit him sometimes. He affectionately stroke my back and told me that I was always welcome to visit him and that his books could be found in the library below the mosque.

I became a regular visitor of the Chakbazar Mosque to listen to Mawlana Faridpuri. It was difficult to find him alone; there would always be 15/20 people around him who used to ask questions about different issues of Islamic jurisprudence and other religious advice and I would learn valuable things from his answers. I didn’t ask too many questions, but would only listen to his conversations with others. After the question and answer sessions finished he would inquire about my well-being and ask which books I was reading and recommend which ones to read next. He later left Boro Katra Madrasah and began a new madrasah at Lalbagh Shahi Mosque.

My communication with Mawlana Faridpuri became infrequent while I was in university. I met him several times after I joined Tabligh Jamaat[1] and attended monthly meetings of Tabligh at Lalbagh Shahi Mosque. Our meetings occurred even less often after I started teaching at Rangpur Carmichael College, though I met him several times for Tabligh programmes. When I used to speak at the monthly meetings of Lalbagh Shahi Mosque I heard that he listened to my speeches with interest. When I went to see Mawlana Fardipuri in 1954 after joining Jamaat-e-Islami, he became very happy and hugged me. Finding everyone surprised he said, “I knew from his speeches in Tabligh Jamaat programmes that the programmes of Tabligh can’t keep him for long.” He asked the people around him, “Didn’t I tell you this?” A number of them said, “Yes, you had said that several times”.

My close relationship with Mawlana Faridpuri contributed immensely towards my development as a Muslim. What I admired most about him was his big heart. The general trend is when people are involved with a type of religious organisation, they usually don’t regard other similar organisations very highly, but Mawlana Faridpuri was an exception who always acknowledged contributions of everyone who served Islam. He used to encourage me while I was in Tabligh, and the encouragement even intensified when I joined Jamaat-e-Islami. When Ayub Khan[2] banned politics in 1959, Jamaat organised Islamic seminars around the country and Mawlana Faridpuri attended several of them as the chief guest. His health was in poor condition, but he still attended some seminars outside Dhaka. His attitude of acknowledging everyone’s contribution towards Islam influenced me greatly and I tried to do the same when I returned to Bangladesh in 1978 after my exiled life. I wrote a book called Islami Oikko Islami Andolon (Islamic Unity and Islamic Movement), the philosophy behind which was the contribution of Mawlana Faridpuri. The most important teaching I received from him was to respect all Islamic scholars. There can be differences of opinions, but one can learn many things from a scholar because of the qualities they possess. That is why I respect all scholars and try to build good relationships with them, even with those who oppose and condemn Mawlana Maududi.

Mawlana Faridpuri took me to speak at different programmes. His concerns for me was at a personal level as well. He once told me, “I can clearly see exhaustion in your face. When I was young like you I was not at all health conscious and due to my negligence towards eating and sleeping I am now suffering from chronic illnesses. I have not been able to fully utilise whatever ability Allah has given me due to my poor health and am wondering how I will answer Allah when He will ask me why I failed to look after the good health He had bestowed on me. You should learn from this bitter experience of mine. Always keep some dry food or fruits with you when you are travelling. Remember to take rest whenever you feel tired. Try to be regular in meals, rest and shower. Always remember that good health is Allah’s blessing and it is your responsibility to look after yourself.” Later in 1957, when political activities were banned during the rule of Ayub Khan, I fell ill and had to be hospitalised. Mawlana Faridpuri came to see me in hospital and said, “I advised you a few years ago about taking care of your health, but you probably didn’t pay much attention to it, and consequently you are in hospital.” I promised him that I would not forget his advice in future, and thankfully, I was able to maintain my health much better after that.

If we had more scholars like Mawlana Faridpuri who could show magnanimity like him then there would have been no problem in unifying all Islamic organisations. Unfortunately, despite having so many Islamic scholars and organisations it is the anti-Islamic forces that are governing the country. That is why I miss a scholar like Mawlana Faridpuri dearly.

Mawlana Noor Muhammad Azmi[3]

It was Mawlana Shamsul Haque Faridpuri who introduced me to Mawlana Noor Muhammad Azmi. When Awami League formed government in East Pakistan in 1956 with Ataur Rahman as Prime Minister and in charge of the Education Ministry, he created an education commission and declared the madrasah education system as useless and a complete waste. I wrote a big article entitled, “A Framework of Islamic Education” to explain the importance of madrasah education. I met Mawlana Akram Khan, the founder of Daily Azad with the article who liked it very much and published it in his newspaper, and later the then editor of the newspaper, Abul Kalam Shamsuddin, wrote a post-editorial on the article appreciating it. It was this article that ultimately led to my close relationship with Mawlana Azmi.

I had been previously introduced with Mawlana Azmi at Mawlana Faridpuri’s office at Lalbagh Madrasah, but did not have the opportunity to be close to him. After the publication of my article Mawlana Akram Khan organised a meeting at his residence and invited Mawlana Faridpuri, Mawlana Azmi, Mawlana Abdur Rahim[4] and others and asked me to join as well. As soon as I arrived Mawlana Azmi hugged me with deep affection and congratulated me for the article. I was really moved by the way he showed his love towards me and gradually our relationship became more and more close.

A ten member ‘Islamic Education Commission’ was formed in that meeting with Mawlana Akram Khan its chair and me its secretary. The committee made some recommendations to the government to Islamise the education system and create a link between the general and the madrasah education. Mawlana Azmi made the biggest contribution to the preparation of these recommendations with Mawlana Faridpuri also contributing well. During that process I had the opportunity to work closely with Mawlana Azmi. I met him many times after that and would often see him for his advice. He loved Jamaat-e-Islami so much that he would be keen to advise Jamaat about different Islamic issues from time to time.

I was always impressed by Mawlana Azmi’s vast knowledge and thoughtful opinions on different aspects of Islam. I found few Bengali scholars at that time of his calibre. His translation and explanation of Mishkat Sharif [5] was of high literary standard. However, for the majority of the time he suffered from ill health and I used to feel bad that he could not contribute as much as he was qualified to due to poor health. When I expressed my frustration to him he said, “I received the impression from the doctor that my illness has no cure, but what is the use of having a long life in this condition? I am, therefore, praying to Allah that He gives Mawlana Mawdudi my part of life as he is serving Islam in such a large scale.” I was not aware before then how much he loved Mawlana Mawdudi and after that then my respect for him increased even more.

Among other Islamic scholars I was close to and always received affectionate love from were the legendary journalist of Muslim Bengal Mawlana Akram Khan and the founder of Nizam-e-Islam Party Mawlana Athar Ali. Other prominent scholars for whom I have deep respect include Mawlana Abdul Aziz (Khulnavi), Mawlana Ziauddin Aligarhi, Mawlana Mufti Deen Muhammad, Mawlana Mufti Amimul Ihsan, Mawlana Abdullahil Baki Al Quraishi, Mawlana Siddiq Ahmed, Mawlana Syed Muslehuddin, Mawlana Syed Mustafa Al-Madani, Mawlana Syed Abdul Ahad Al-Madani and Mawlana Tajul Islam (may Allah be pleased with all of them).

The close bond I had with Mawlana Shamsul Haque Faridpuri and Mawlana Nur Muhammad Azmi (may Allah be pleased with them) and the love and affection I received from these two great scholars have contributed hugely towards my work and development in the cause of Islam. I have come across many scholars of Islam in my life, but I remember these two individuals with special love and respect. They had the magnanimity of acknowledging the contribution of any person who had served Islam. I never heard them talk ill of others. They sincerely wanted the movement for the establishment of Allah’s Deen[6] to be on the right path and would always give me valuable advice. I have always felt that their thoughts on Islam were exactly in the same line.

[1] An Islamic religious movement based on the principle of the “Work of the Prophets” inviting to Allah in the manner of prophet Muhammad (PBUH).

[2] President of Pakistan in 1950s and 1960s

[3] Another prominent Islamic scholar of that time, contemporary to Mawlana Faridpuri

[4] Former President of Jamaat-e-Islami of the then East Pakistan

[5] A revered book of hadith compilation

[6] The path along which righteous Muslims travel in order to comply with divine law

My Journey Through Life Part 9

MY JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE

BY

PROFESSOR GHULAM AZAM

(Abridged Translated version of the author’s original Bangla Memoir Jibone Ja Dekhlam)

Translated and Edited by Dr Salman Al-Azami

Copyright – The Ghulam Azam Foundation

Chapter Nine

Growing Up as a Muslim

I was 19 when I completed my high madrasah education in 1942. I learned how to read the Qur’an before my primary education and continued to read the Qur’an in this way for 13 years. I learned Bangla, English and Arabic in whatever way I could in those years and learned about Islamic jurisprudence and customs through books and translations of the Qur’an and hadith[1]. I also learned about moral values from some books in Bangla and English. However, there was no book on Islam that would provoke my thoughts, so whatever I learned and practiced about Islam was outside my educational experience.

My grandfather helped me develop the practice of regular prayers and daily recitation of the Holy Qur’an. He also taught me some essential Islamic food etiquettes, such as starting to eat by saying Bismillah[2], ending the meal with Alhamdulillah[3], not wasting food etc. While staying in student halls I could guess fellow students’ family backgrounds by their food etiquettes. Some had very annoying habits which made me feel the importance of learning these etiquettes during childhood, as it is difficult to teach such things when people grow older.

Attraction for Waz[4]

I don’t know why, but I loved to listen to waz from childhood and used to organise children of my age to walk a few miles to attend waz programmes. The speakers at that time would quote poets like Sheikh Saadi and Mawlana Rumi more than quoting from the Qur’an and hadith. They would recite works of those Persian poets in such beautiful melodies that we enjoyed them even without understanding what they meant. Their explanations of those poems and the lessons behind them were very catchy and I used to feel how they influenced me in my life. The teachings of those wonderful stories, such as the importance of truthfulness, the dangers of telling lies, the negative effects of causing harm to others; the humiliating consequences of breaking promises and so on would be explained so eloquently that I realised how some of these vices could lead to troubles in this life.

Almost all speakers used to narrate the story of Adam (PBUH[5]) and Iblis (Satan). Instead of finding them inspiring, some fundamental questions arose in my mind that no one could answer satisfactorily. These questions made me feel very uncomfortable, but I couldn’t find their real answers until I read works of Mawlana Mawdudi[6]. Some of these questions include:

- Allah secretly taught Adam (PBUH) answers to some questions that the angels failed to answer. Does this mean Allah was not impartial?

- Many people narrate the story that if Adam and his wife Hawa (peace be on them) did not eat the forbidden fruit then they would have stayed in heaven forever. If that is true, then what about Allah’s declaration that He created human beings as his representatives on this earth?

- If Adam (PBUH) was sent to this earth as a punishment then how did he acquire the status of prophet?

I found brilliant answers to all these questions that used to bother me in Tafhim-ul-Qur’an[7] and thought of writing on this issue separately. While I was in jail in 1992-93 I wrote a book named Adam Srishtir Hakikot (The Significance of Adam’s Creation) where I analysed the seven places in the Qur’an where the story of Adam (PBUH) and Iblis are narrated. I tried to prove that the real significance of this story is very different from that which is commonly narrated in waz programmes.

Interest in Islamic Literature

As already mentioned, there were no textbooks that succeeded in enlightening me with the knowledge of Islam as a way of life, and the books I used to borrow from my madrasahs’ libraries were of no use either. When I was in Class 8 in Comilla a student two classes senior to me called Abdul Qayyum used to live as a tutored lodger in a house on the way from my madrasah. He used to call me and my friends to his room and give us some snacks to eat and read to us from a monthly magazine. I started to like the content of the magazine after a few visits and came to know that it was a Dhaka-based monthly magazine called ‘Neyamot’. It used to contain translations of waz by Mawlana Ashraf Ali Thanvi[8] (may Allah be pleased with him) translated by Mawlana Shamsul Haque Faridpuri[9]. Abdul Qayyum never let us borrow his books; he preferred to read them aloud to us. Most students stopped calling on his residence after a few days, but I found my visits very fascinating and continued to visit him.

I was very impressed by the waz of Mawlana Thanvi. He used to recite a particular portion of the Qur’an followed by its translation and explanation in a very logical style giving us a clear idea about the main aspects of those verses. The monthly Neyamot would consist of one topic from his waz every month. I was so overwhelmed by this that I would eagerly wait for each new edition and until it arrived Abdul Qayyum would read to me from other books by Mawlana Thanvi. I can never forget the contribution of Abdul Qayyum in creating my interest in Islamic literature, through which I was exposed to the writings of both Mawlana Thanvi and Mawlana Fardipuri. When I started Class 9 in Dhaka I went to the monthly Neyamot office and became a subscriber. I developed a good rapport with its editor, Mawlana Abdus Salam, who was from my own district of Brahmanbaria. It was he who introduced me to the great personality of Mawlana Shamsul Haque Faridpuri.

Until then I understood Islam as a religion from my parents and grandparents and obeyed their orders in practising it. Although Mawlana Thanvi’s books gave me the confidence that Islam was a logical religion, I was still not aware that it was a complete way of life. However, Mawlana Thanvi’s greatest contribution to me was that he created my thirst for learning Islam.

Strict Practice of Islam at Home

My father was uncompromising about the practice of Islam in our daily lives. The following are some examples:

- Praying in congregation: When I was in Chandina the mosque was a little far from our house. He used to pray five times at the mosque and encouraged us to do the same. He would become angry if we sometimes failed to go to the mosque. When we moved to Dhaka in 1953 he used to pray regularly at the mosque next to the Ramna Police Station. The distance to the mosque in Dhaka was similar to that of Chandina. When my eldest son was in Class 6 he arranged prayers in congregation at home. The first reason was that he found it difficult to walk to every prayer due to his arthritis, and secondly he wanted his grandson to grow the habit of praying in congregation. He subsequently decided that he would build a mosque on his property in Moghbazar. He realised that it would be difficult to take all his grandchildren to the mosque near Ramna Police Station, so it was necessary to have a mosque at home. The first floor of the present three-storeyed Moghbazar Kazi Office Lane Mosque was built entirely from his own expenses without any external help. The mosque began operating from the first day of Ramadan in 1971.

- Keeping a beard: My youngest uncle, Mr Shafiqul Islam, was three years older than me. When I was in Class 8 in Comilla in 1939 he was studying in Dhaka Government Intermediate College. My father noticed when he came to Chandina that my uncle had started shaving his beard. My father told him, “It is Sunnah[10] to keep a beard and Allah has made this for men only. If you don’t keep a beard then it means that you prefer to be like a woman. I want you to keep a beard and if you don’t then I will have to stop paying for your education.” When my uncle came home the following summer with a bearded face my father became extremely happy, hugged my uncle and said to him with tears in his eyes, “If you follow the path of Allah and His Prophet then you will succeed in both the worlds.” My mother also joined the celebration and held a mirror in front of my uncle saying, “See, how handsome you look!”

This incident of my uncle made such a big impact in our family that all those who were dependent on our father – we four brothers and the first two sons of our eldest uncle – kept a beard from the beginning. I first grew a beard in 1942 when I started Islamic Intermediate College. Initially I had some scattered facial hair, so some of my friends suggested that to make my beard look good I should shave it for a while. I remember that one of my roommates shaved my beard a few times, which made my conscience hurt. I didn’t let him continue this as I was supposed to go back home in a couple of months. When I returned to the hostel after the summer holidays my beard was big enough to be noticed. Although some of my friends were not happy to see me with a beard, a number of them felt encouraged to keep a beard themselves. One of them said, “We decided to keep a beard looking at you. We had also thought that we needed to shave for a while to make the beard look good, but your beautiful beard changed our minds.”

I found very few students with a beard in university. Even students of Arabic and Islamic Studies hardly had a beard except those who came from madrasahs. The only prominent academic with a beard was Dr Muhammad Shahidullah. After retirement Dr Shahidullah used to run a Qur’an class in the prayer room of Fazlul Haque Muslim Hall, which I used to attend regularly. He was a short man, but his beard was quite big compared to his physique. One day, he held his beard in his fingers and asked, “How much does my beard weigh?” When students found this question quite surprising he said, “Then why do most of you shave your beard? Do you think it is too heavy?” He also said that people look at bearded people with respect. This I found to be very true throughout my life. During my terms at the Dhaka University Student Union I used to notice that students would behave more gently when I was around. Even the only female member of the union would cover her head when I used to come to the union office.

- Wearing clothing above the ankles: My father would never hesitate to suggest to people not to wear clothes below the ankles. As there are strong words against it in the hadith, he was justified to put emphasis on this. None of my classmates were concerned about this, so my clothes also used to be below the ankle. I would only raise clothes above the ankle before prayer and roll them back after finishing the prayer. However, we never dared to wear clothes that crossed the ankle in front of my father. We would pull our pyjama bottoms up to ensure that they were above the ankle before we met him and go back to the previous position afterwards. This behaviour was completely unacceptable. After reading the book Witness unto Mankind by Mawlana Maududi I realised that this type of behaviour is normal if one is not fully aware of what Iman (faith) means and does not develop the true spirits of Islam. I stopped wearing clothes below the ankle as soon as I became truly conscious about Iman and Islam.

- Wearing shirts and trousers: No one in our family was used to wearing shirts and trousers. My uncle Shafiqul Islam was a student leader during the Pakistan movement and used to stay in the famous Bekar Hostel of Kolkata while studying at Kolkata Presidency College. Yet he would always wear pyjama bottoms[11] and shirts and never wore shirts or trousers. When my younger brother started hospital duty in the third year of his medical college studies in Kolkata Medical College, he wrote a letter to my father seeking permission to wear trousers. He didn’t dare to wear trousers himself without my father’s permission due to my father’s uncompromising attitudes towards religious practice. My brother thought it was necessary to avoid his long shirt touching the patients and as it would look very odd to tuck his shirt inside his pyjama bottoms, he thought it would be better to wear trousers. My father replied, “If you can’t study medicine without wearing trousers, then it is better to leave this subject.” With the grace of the Almighty this brother of mine passed with a gold medal award wearing pyjama bottoms and shirts throughout his student life.

I too spent my university life, including my roles at hall and university unions, wearing pyjama bottoms and shirts although most of my fellow students used to wear shirts and trousers. When I started my teaching career at Rangpur Carmichael College in December 1950 I found it very difficult to keep myself warm with pyjama bottoms and shirts, so I had to wear warm trousers and a sherwani[12]. I ensured that my tailor stitched the trousers above the ankle. When I arrived back home for holidays wearing sherwani and trousers I found my brother Dr Ghulam Muazzam and my father sitting on the veranda. I observed that my brother was staring at my trousers and then looking at my father. After doing that for several times my father understood what he was thinking. He said to my brother, “I never considered wearing trousers to be haram[13], but had thought that trousers are always worn below the ankle. I was unaware that it was possible to wear trousers above the ankle. That is why I didn’t give you permission to wear trousers. I have no problem if you wear trousers above the ankle. However, although wearing shirts is permitted in Islam, I don’t like it.” After this my brother also started wearing trousers.

When Dr Ghulam Muazzam went to London for higher studies he took with him warm trousers and a sherwani. One of his classmates told him that he would not be given his degree if he didn’t wear a suit. I heard from my brother that his individuality was rather appreciated and he was always praised as a good student. When Dr Muazzam was working as a pathologist at Dhaka Medical College, the principal once told him, “You should come properly dressed.” Dr Muazzam asked him, “What dress is proper according to you?” The principal, in a rude voice, said, “Don’t you see what other doctors wear?” Muazzam replied in a firm voice, “I have seen sweepers wearing that type of dress in England. It is their national dress, not the uniform of a doctor.” The principal preferred to remain silent after this.

Some people may not like my father’s strict attitude towards religious principles, but the lessons I had from this have been extremely valuable for me. We do everything for our children’s worldly successes and never hesitate to sacrifice for them, but how many parents are serious about their success in the hereafter? I have seen many pious people not even bothering to ensure that their children pray five times a day and not worried if their daughters don’t wear the hijab. They are only happy if they do well in their exams and succeed in this world. They forget that they will have to answer to Allah on the Day of Judgment if their children are derailed due to their negligence. If my father had not been strict then it would have been difficult for his children to lead an Islamic lifestyle being brought up in a secular educational environment. There is little scope of bringing up our children as a Muslim in our general educational system. Those who are able to live as a Muslim have been able to do so only because of their parents’ influence.

[1] Teachings of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) including sayings, actions and tacit approvals.

[2] In the name of Allah

[3] All praise is to Allah

[4] A traditional Islamic gathering with massive attendance in Bangladesh with an Islamic scholar speaking about different aspects of Islam and narrating stories about the prophet and his companions.

[5] Peace be upon him

[6] A renowned Islamic thinker and founder of Jamaat-e-Islami

[7] ‘’Towards Understanding the Qur’an” translation and explanation of the Qur’an by Syed Abul Ala Mawdudi

[8] A prominent late 19th and early 20th century South Asian scholar from the Deobandi school of thought.

[9] A famous 20th century Islamic scholar in East Bengal

[10] Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)

[11] A type of trousers worn in Bangladesh as distinct from the salwar bottoms worn in Pakistan.

[12] A knee-length coat buttoning to the neck, worn by men from South Asia.

[13] Forbidden in Islam

My Journey Through Life Part 8

MY JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE

BY

PROFESSOR GHULAM AZAM

(Abridged Translated version of the author’s original Bangla Memoir Jibone Ja Dekhlam)

Translated and Edited by Dr Salman Al-Azami

Copyright – The Ghulam Azam Foundation

Chapter Eight

University Education

I passed my Higher Secondary Exams (IA) in May 1944. In undivided Bengal all the general colleges of Dhaka city and all Islamic Intermediate Colleges of Bengal were under the Dhaka Board; the rest were under the Kolkata Board. Seven out of the first ten winners of first grade scholarship in Dhaka Board were from Islamic Intermediate College – myself included. All of us who passed from this college that year enrolled in Dhaka University, which was the only university in East Bengal. There were five colleges in Bengal at that time known as ‘premier colleges’ of which four were from East Bengal. The four premier colleges in East Bengal were Comilla Victoria College, Barisal BM College, Rangpur Carmichael College and Mymensingh MM College. The only premier college in West Bengal was Kolkata Presidency College.

Which Subject to Study?

Many people nowadays plan long ahead which subjects they would study. There was no such plan at least by me at that time. My father always emphasised one thing – to master Bangla, English and Arabic, which according to him was the mantra of success in all aspects of life. There was no plan about my future career, so the question arose which subject I should choose to study at university. It was mandatory for scholarship holders to study a three-year Bachelor’s degree with honours, without which the scholarship would be cancelled. To help in making a decision I, along with some friends, approached our favourite English teacher Syed Mainul Ahsan at his residence in Nazimuddin Road. I was thinking of studying either English Literature or Political Science for my degree, but our English professor spoke for ten minutes encouraging us to study Arabic. The logic he attempted to give was to take a subject that would enable us to get high marks that would lead us to a good government job.

Hindus at that time were much more advanced than Muslims in education, for which reason it was difficult to compete with them in the job market, particularly in the academic sector, so the government sector would be preferable. As a Muslim-majority state the Muslim government of East Bengal were keen to have people from the community in government positions, but it was difficult to exceed the Hindus by competing with them. He said, “As you are good students you should target the civil service and studying Arabic will give you more opportunity to score highly and do better in the competition.” He suggested that subjects like English, Economics, Political Science etc. can be taken as minor subjects. The Pakistan movement had not found much momentum then and there was no sign of the establishment of Pakistan – a separate state for Muslims – so in that situation we found his arguments logical and we all decided to study Arabic. I chose English and Political Science as my minor subjects.

Choosing a Student Halls

Dhaka University has been a residential university since its inception, so the majority of its students stay in one of the student halls. Those who don’t stay in halls also need to be attached to one of the halls. Both residents and non-residents of a hall could vote in the hall union elections. There were four student halls at that time, two for Hindus and two for Muslims. The university started with two halls – Salimullah Muslim Hall and Jagannath (Hindu) Hall and later Fazlul Haque Muslim Hall and Dhaka (Hindu) Hall were opened.

I didn’t choose Salimullah Muslim Hall despite its reputation and beautiful architecture; I didn’t like the halls being scattered in different places. I decided to stay in Fazlul Haque Muslim Hall as it was near the building where the classes were held. Thus my university life began as a resident of Fazlul Haque Muslim Hall in July 1944. The provost of the Hall at that time was Dr Mahmud Hossain, who was a Reader in the History department and later became the Vice Chancellor of the university. I last met him in 1957 while he was working at Karachi University. He loved his students very much and used to speak to them frankly. He was originally from Delhi and was once elected in Pakistan Parliament as a representative of East Pakistan. His elder brother was the renowned educationalist Dr Zakir Hossain who founded Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi. He was also the Vice chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University and became the President of India during the premiership of Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru.

There were two house tutors in Fazlul Haque Muslim Hall. One of them, Dr Mazharul Haque, was a lecturer in Economics (and later became a prominent economist). Dr Haque called me in his office one day and asked me, “Why did a talented student like you choose to study a degree in Arabic? Generally only those from madrasah background study Arabic and some choose it as an easy subject to get a university degree. You did the opposite. You chose English and Political Science as your minor subjects, but Arabic as your major subject. I am surprised!” When I related the reasoning behind my decision he commented, “It was the wrong advice from your English teacher.”

University Lectures

I was very enthusiastic about the lectures in university as I had a very good impression of university lecturers. The distribution of marks in my degree was 800 for honours in Arabic, 300 each for the two minor subjects English and Political Science, and 100 for Bangla – compulsory for all students in the university. All teachers in English, Bangla and Political Science were Hindus and their lectures were very enjoyable. I used to note down the summary of these lectures with great care, which would be very useful during my exams. Teachers would ask questions in class that also contributed well towards my notes. Our English teacher took five days to talk about Shakespeare before introducing his works. Similarly our English poetry teacher would first talk about poets like Wordsworth, Tennyson, Byron and so on before discussing their poems. The lectures of Political Science were also very interesting and I could feel that I was learning something. A lot could be learned from my Bangla teachers as well. I would ensure that I never missed any lectures of these three subjects. It became my passion to attend all lectures irrespective of any other commitments and take down notes of each lecture. I never missed a lecture even when I was actively involved with the hall union. If I ever missed a session due to illness, I would make sure that I copied class notes from the better students in class.

The lectures I felt most uncomfortable with were my Arabic classes. The only class I enjoyed was Islamic Philosophy, taught by an Indian professor named Syed Jilani. Those who taught Arabic poetry and prose hardly gave lectures, but would merely read out English translations of the texts and give us dictations. It was not helpful to learn Arabic at all. I had expected them to give lectures in Arabic, as done by the English teachers in English classes, but it was not to be. They never gave lectures in Arabic and would just read out the Arabic of textbooks. There were no printed translations of the Arabic texts at that time as no publisher found it a lucrative business proposition. Therefore, teachers would read out the notes they had written and we would copy them. I used to consider it a complete waste of time as I could get the meanings of words from the dictionary myself. Although the Arabic grammar teacher was good, what use is there in grammar if it doesn’t facilitate language learning? Grammar does not teach a language, it merely corrects the mistakes. Without competence in language I found the grammar lessons meaningless. There was a textbook by Abdur Rahman Awqabi who tried to copy the style of the Qur’an in his book. The teacher used to recite the book as if he was reciting the Qur’an. Hearing this, some badly-behaved students used to say, Subhan Alla[1], Marhaba[2] etc. The teacher never felt embarrassed that the students were making fun of him. He never spoke anything about its content other than dictating its translation to us. This continued for six months and my irritation towards my Arabic classes continued to rise.

I strongly felt that taking Arabic as a major subject was of no use. I felt no progress in my command over the Arabic language since I left college. I tried to explore the possibility of changing my major subject. The other two options I had for a major subject were English and Political Science. I felt more inclined towards political science and approached the head of the department Professor D N Banerjee. He was happy that I wished to major in his subject, but told me that it was too late for that year, so I had to wait until July the following year to enrol in the department. I became very worried. I was neither ready to lose another year from my academic life, nor was I happy to continue with Arabic. I also came to know that if I chose pass course degree[3] instead of an honours degree then I would lose my scholarship and would also need to pay fees for my studies, which were exempted due to my scholarship. I went back home to Chandina for the winter vacation with this dilemma.

I was unsure how my father would react to my decision. He had been exceptionally glad when I chose to major in Arabic. I was not certain whether or not he would allow me to leave the subject. The other problem was that he would now have to pay for my educational expenses as I would lose my scholarship. I took a good few days to prepare myself how to approach my father. I was so anxious that my food and sleep were affected. My father noticed this condition of mine and asked me one day why I looked so tense. I couldn’t say a word and tears began to roll down my cheeks. My father became very concerned. I then told him everything. It was a big relief when he replied; I was overwhelmed by his confidence in me. He said, “I only want you to do well in your studies. Financial losses don’t factor to me at all. It is not possible to study a subject without feeling comfortable about it. Whatever decision you take I will support you.” I felt a heavy burden released from my shoulders and I decided at once that I would not lose another year and would complete my degree in pass course and then do a master’s degree.

University Environment

The two-storied hall building of Fazlul Haque Muslim Hall (now three-storied) had student accommodation on three sides and the southern side had a big gate, which had the offices and residences of the two house tutors on its two sides. There was a pond on the western side of the hall and on its other side was the Dhaka Hall for Hindus (now Shahidullah Hall). There was no scope to take shower inside the halls at that time, so students used to bathe in the pond.

I really liked the hall environment. There was a wonderful tradition of juniors respecting the seniors, for example, by letting the seniors sit on the dining table first, making way for them while walking, giving the seniors priority while having bath in the pond and letting them jump the queues for the toilet. The environment was so nice that the seniors would often forfeit their advantages and would affectionately let the juniors enjoy a particular privilege. If they would take the privilege due to time constraints they would never forget to thank the juniors for their generosity. Good students used to get special treatment and juniors used to greet them with special respect. This type of environment is unthinkable in modern times. Even the teachers hardly get this type of respect. While attending the 40th anniversary of Fazlul Haque Muslim Hall in 1979, I asked the then provost Dr Mohabbat Ali what type of respect he received from his students compared to the older days. He replied in a sad voice, “I just somehow manage to maintain my dignity”.